Report: Beijing's civilian maritime militia dominates the seas and oceans. Exposing and intercepting it to prevent spying is imperative

- Nicola Iuvinale

- 15 apr 2024

- Tempo di lettura: 53 min

Abstract

The case of Sansha City is strong evidence of the existence of China's civilian maritime militia. It was discovered in 2021 that the state-owned fishing company responsible for Sansha City's maritime militia fleet managed projects involving classified national security information, a strong indicator that the company's ships are engaged in more than just fishing. In addition to monitoring the fleet owned by this company, there is evidence that one of its ships has been used to test an experimental command and communication system built with foreign technology, which likely turned the ship into a mobile communication and surveillance platform capable of transmitting information to authorities ashore. Some of the communication technologies installed on ships in the "Qiongsanshayu" fleet also indicate that they are more than just fishing vessels. According to a February 2018 environmental impact assessment, the Hainan Communications Administration recently conducted a project to test an "emergency satellite command and communication" system aboard a vessel for maritime law enforcement, fisheries and emergency management in the South China Sea. The ultimate goal of this project was to build satellite links between shipboard systems, land-based communications networks and an emergency command center, effectively extending information flows to and from distant areas of the disputed South China Sea. The experimental system on Qiongsanshayu 00209 also uses foreign satellite technology from companies in the United States, South Korea and Japan and other. China could leverage a U.S. defense contractor's counter-surveillance technology to protect city communications from U.S. signals intelligence collection efforts. U.S. intelligence collection in the South China Sea region has long irked the PLA, which maintains numerous sensitive facilities in the area, from submarine bases to missile sites. Over the past 20 years, Chinese forces have repeatedly intercepted U.S. intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance platforms operating in or above the South China Sea. These interceptions have caused serious accidents on several occasions, such as in 2001, when an EPL fighter jet crashed into a U.S. EP-3 intelligence plane, killing the Chinese pilot and forcing the U.S. plane to make an emergency landing in Chinese territory. However, the use of civilian maritime entities for military use is not a phenomenon limited to Chinese vessels sailing in the South China Sea. China has the largest military and civilian navy in the world. An ancient adage goes "he who rules the seas, rules the world." Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, China's main goal has been global hegemony: to make Beijing the world's leading power in trade and military. On July 3, 2023, at a conference at the Senate of the Italian Republic entitled "The Future of NATO and the Role of Italy," organized by the Comitato Atlantico Italiano spoke about China's Liminal Warfare and the use of Chinese civilian maritime entities for military use. To achieve this goal, Beijing is also exploiting the Belt and Road, including maritime. To support force projection abroad, Beijing has developed a military strategy that requires the armed forces to routinize military activities across borders, encouraging the use of BRI investments, especially in ports, airports and railways. The 2015 Defense White Paper makes explicit Beijing's growing commitment to protect its foreign economic interests in the context of broader civil-military fusion. Civilian organizations (public and private) are to contribute to PLA operations through the provision of dual-use technologies and the provision of maritime civilian entities (ports and ships). As of 2019, Chinese SOEs including COSCO operated about 70 ports outside China; by 2022 that number is believed to be more than 100. In Europe they are: Euromax in Rotterdam, Antwerp in Belgium, Hamburg in Germany, Piraeus in Greece and Vado Ligure in Italy. China COSCO Shipping operates more than 360 container ships, with the third largest container fleet capacity in the world. According to U.S. military strategists, most of the aforementioned locations could host PLA ships for refueling because they are located near airfields or air bases, or could be used as logistics hubs for cargo ships or tankers, which could then refuel Chinese military ships offshore, including in the Mediterranean. Finally, with the development of the modern logistics industry, containers are increasingly entering people's field of vision. They can be found on trucks, trains, and docks along the coast. Containers are increasingly appearing on the battlefield. However, in addition to their basic function of transporting materials, many of these containers exist as weapons and some have even been used in actual combat. Those containers masquerading as civilians may contain Chinese offensive weapons and may already be found, unbeknownst to us, in many ports of Western and NATO countries.

by Nicola e Gabriele Iuvinale

On July 3, 2023, at a conference at the Senate of the Italian Republic entitled "The Future of NATO and the Role of Italy," organized by the Comitato Atlantico Italiano spoke about China's Liminal Warfare and the use of Chinese civilian maritime entities for military use.

On the occasion i said that "history teaches that whoever controls the maritime traffic controls the world." To support force projection abroad, Beijing has developed a military strategy that requires the armed forces to routinize military activities across borders, encouraging the use of BRI investments, especially in ports, airports and railways.

The 2015 Defense White Paper makes explicit Beijing's growing commitment to protect its foreign economic interests in the context of broader civil-military fusion. Civilian organizations (public and private) are to contribute to PLA operations through the provision of dual-use technologies and the provision of maritime civilian entities (ports and ships).

First articulated in 2004 by Beijing's military strategists, the "String of Pearls" theory argues that commercial port facilities can also serve as cover for ammunition depots, supporting combat operations. Chinese commercial ties with host countries can also result in secret agreements to allow the Chinese Navy access to facilities in the event of armed conflict. Plenty of bilateral BRI agreements China has signed with European countries, including NATO, contributing to the de-escalation of the Union's political and control action. In June 2015, China issued Technical Regulations for the construction of civilian ships that impose standards to enable their convertibility to military use.

Civilian shipping companies have repeatedly emphasized the importance of contributing to the national defense effort by participating in exercises and adapting ships for military use. In addition to ships, civil-military fusion in the liminal warfare perspective also affects foreign civilian port facilities. China already frequently uses civilian ports for docking and refueling in military missions in the Gulf of Aden.

Colonel Cao Weidong, of China's Naval Military Research Academy in 2013 said, "In the Mediterranean region COSCO, China's state-owned naval conglomerate, has many refueling points, which provide daily services for civilian ships. Chinese warships can also enter ports for supplies."

As of 2019, Chinese state-owned enterprises including COSCO operated about 70 ports outside China; by 2022 that number is believed to be more than 100. In Europe they are: Euromax in Rotterdam, Antwerp in Belgium, Hamburg in Germany, Piraeus in Greece and Vado Ligure in Italy.

China COSCO Shipping operates more than 360 container ships, with the third largest container fleet capacity in the world. According to U.S. military strategists, most of the aforementioned locations could host PLA ships for refueling because they are positioned near airfields or air bases, or they could be used as logistical hubs for cargo ships or tankers, which could then refuel Chinese military ships offshore, including in the Mediterranean. What then are the major risks to NATO countries?

First, Chinese state-led investments generate a risk for the host state: getting caught in Beijing's military disputes. Ports, if used for military missions would put the host state in the difficult position of either accepting Chinese military operations in its territorial waters and risking retaliation from Beijing's military rivals or, conversely, rejecting Chinese military operations and suffering retaliation from Beijing. Second, port states hosting Chinese state investments are targets for espionage.

Ports are, in this case, rich targets in both military and commercial terms. Third, Chinese state-led port investments are vehicles for economic coercion. In times of political conflict between China and the state where the port is located, Beijing can disrupt port operations, or initiate vexatious litigation or contract termination. This creates pressure on port states while also limiting their political autonomy.

Unmasking China’s Maritime Militia. How China is Leveraging Foreign Technology to Dominate the South China Sea. The case of of the city of Sansha is clear evidence of the existence of China's civilian maritime militia. Report by Radio Free Asia

China has long denied that it uses maritime militia forces to assert its maritime and territorial claims in the South China Sea, often describing the Chinese vessels clustered around disputed reefs and islets as just fishing boats.

But the paper trail left by the Chinese bureaucracy tells a different story.

Radio Free Asia analyzed bidding documents, corporate records, and other official data in an effort to shed new light on the maritime militia belonging to Sansha City, a municipality under Hainan province that administers China’s claims in the South China Sea from its headquarters on Woody Island in the Paracels.

RFA found that the state-owned fishing company in charge of Sansha City’s maritime militia fleet has managed projects involving classified national security information, a strong indicator that the company’s ships are engaged in more than just fishing.

In addition to tracking the fleet owned by this company, RFA also uncovered evidence that one of its ships was used to test an experimental command and communications system built with foreign technology, which likely transformed the vessel into a mobile communications and surveillance platform capable of transmitting intelligence back to the authorities on land.

Map of the South China Sea highlighting major Chinese outposts under Sansha City’s jurisdiction in the Paracel and Spratly islands. Credit: Google Earth; Analysis: RFA

And referencing the corporate records of fishermen legally registered in Sansha City against Chinese state media reporting on the city’s militia, RFA further verified that numerous "fishermen" living in Sansha are actually militiamen responsible for guarding China’s outposts.

China’s maritime militia has been in the news. The presence of numerous maritime militia ships at Whitsun Reef in the Spratly Islands in late March set off a diplomatic tussle between Beijing and Manila and prompted widespread international criticism of China, despite its assertion that these were just fishing vessels sheltering from poor weather.

“Recently, some Chinese fishing vessels take shelter near Niu'e Jiao [Whitsun Reef] due to rough sea conditions,” said a spokesperson for the Chinese Embassy in the Philippines. “It has been a normal practice for Chinese fishing vessels to take shelter under such circumstances. There is no Chinese Maritime Militia as alleged,” the spokesperson stated.

But multiple open-source investigations have confirmed the presence of militia vessels near the reef.

Now, RFA is taking a step further to shed light on the true nature of China’s maritime militia, pulling back the curtain on the procurements, fleet, and personnel of this shadowy paramilitary force.

Classified projects

Sansha City established its new maritime militia in 2013 on the basis of the original Paracel Islands militia. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Hainan Province Sansha Garrison on Woody Island took charge of training and commanding this new force, according to numerous reports in Chinese state media.

Militiamen swearing oaths during the founding of Sansha City’s maritime militia in July 2013. Credit: China National Radio

By July 2016, the city’s maritime militia had grown to include over 1,800 militiamen and more than 100 vessels, the Sansha City government reported. At the time, the municipal authorities described this force as playing an “irreplaceable role” in defending China’s maritime claims.

China’s expansive claims in the South China Sea overlap with claims from five other states — Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Brunei — and are a source of significant tension in the region.

According to a 2015 article authored by Sansha Garrison Commander Cai Xihong in the PLA-run magazine National Defense, the city created Sansha City Fisheries Development Co, Ltd. to manage the militia’s new fleet of steel-hulled ships. Corporate records confirm that Sansha established this new municipal state-owned enterprise in February 2015.

Sansha Garrison Commander Cai Xihong reading out orders during the founding of Sansha City’s maritime militia in July 2013. Credit: China National Radio

Sansha City Fisheries Development regularly invites other companies to bid on contracts to supply goods and services to the company. RFA found two such projects from 2017 with either “classified information systems integration” or “state secrets protection” credentials requirements for the third-party supplier. These security qualifications are typically reserved for companies and other entities working on classified projects for the PLA or the Chinese government, which suggests that Sansha City Fisheries Development is indeed the civilian front for a paramilitary force.

In late 2017, Sansha City Fisheries Development hired Xi’an Jiangong Construction Tendering Co., Ltd. to manage the bids for a “fishing boat hull underwater cleaning project” worth 5,628,640 yuan ($804,000). One announcement published by Xi’an Jiangong Construction Tendering during the bidding process states that the project “involves national security and secrets” and another specifies that the third-party supplier must have a “state secrets protection” qualification.

And earlier in 2017, Sansha City Fisheries Development tendered bids for a “special equipment” contract worth 63,710,000 yuan ($9,101,400) for an “SX command system.” According to the tendering announcement, the third-party supplier needed to have a “classified information systems integration first-class credential” or a “national third-level or higher secrets protection qualification.” The former covers the development, construction, and operation of classified information systems at the top-secret level; the latter covers weapons and equipment research and development projects at the lowest classification level, Chinese regulations say.

The company that won the “SX command system” contract is Space Star Technology Co., Ltd., also known as the CASC 5th Academy 503rd Research Institute, a subsidiary of the state-owned defense contractor China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC). Though the technical details of the “SX command system” remain unclear, Space Star Technology’s website and contracts reveal a range of comparable capabilities, including military intelligence equipment as well as maritime communications and command systems. One specific example is a South China Sea monitoring system through which law enforcement ships and fishing boats from Guangdong province can collect information and transmit it back to a command center on land in support of the defense of China’s maritime claims.

If Sansha City Fisheries Development really were a civilian fishing enterprise, why would the maintenance of its ships involve national security and state secrets? And why would a fishing company need to procure a highly classified information system from a state-owned defense contractor? These are clear indicators of the company’s militia connection.

A suspicious fleet

In addition to digging up these classified projects, RFA found evidence confirming that Sansha City Fisheries Development manages a fleet of steel-hulled ships belonging to Sansha City’s maritime militia.

Each of the vessels in this fleet operates under the name of “Qiongsanshayu” followed by a string of numbers. As per Chinese naming conventions, “Qiong” indicates that the ships fall under the jurisdiction of Hainan province, “sansha” conveys that they belong to Sansha City, and “yu” marks them as ostensible fishing vessels.

The Qiongsanshayu 00310 participating in a joint exercise with forces from Sansha City in July 2016. Credit: Xinhua News

A Chinese government document that RFA reviewed explicitly describes one of these “Qiongsanshayu” vessels as belonging to Sansha City Fisheries Development.

Using the automatic identification system (AIS) data from the MarineTraffic ship-tracking platform, RFA identified 40 vessels operating under the name of “Qiongsanshayu” whose behavior reveals ties to Sansha City Fisheries Development.

Over the past year, each of these 40 vessels has operated from at least one of three ports on the Hainan mainland: Sanya Yazhou, Wenchang Qinglan, and Danzhou Baimajiang.

Map showing the Sanya Yazhou, Wenchang Qinglan, and Danzhou Baimajiang ports in Hainan. Credit: Google Earth; Analysis: RFA

According to Chinese government land-use records, Sansha City Fisheries Development has long-term rights to space at each port. And bidding records show that the company has been actively developing its facilities at all three ports.

During 2020, 16 of the 40 “Qiongsanshayu” ships sailed to a shipyard owned by Zhanjiang Haisheng Shipbuilding Co., Ltd. in Guangdong province. Sansha City Fisheries Development hired Zhanjiang Haisheng Shipbuilding for a “2019-2020 fishing boat maintenance project” in early 2019, bidding records show.

AIS data superimposed over a satellite image from August 2020 showing the Qiongsanshayu 000210 visiting the shipyard run by Zhanjiang Haisheng Shipbuilding in June, July, and August 2020. Credit: MarineTraffic; Analysis: RFA

Satellite imagery confirms the AIS data gathered by RFA, revealing organized rows of matching 60-meter-long steel-hulled fishing vessels at Sanya Yazhou, Wenchang Qinglan, Danzhou Baimajiang, and the Zhanjiang Haisheng Shipbuilding shipyard.

A proposal submitted to the Hainan authorities in 2015 suggests that Sansha’s militia fleet has at least 84 vessels.

Satellite image from January 2021 showing rows of matching 60-meter-long fishing vessels lined up in an area of the Wenchang Qinglan harbor used by Sansha City. Credit: Google Earth

Beyond Sansha Garrison Commander Cai Xihong’s admission that Sansha City Fisheries Development manages the city’s militia steel-hulled fleet, several pieces of evidence connect the “Qiongsanshayu” fleet and its facilities to Sansha City’s maritime militia.

Procurement records from the Sansha Garrison — which is responsible for training and commanding Sansha’s maritime militia — reveals the presence of dedicated “militia bases” with training facilities near both the Sanya Yazhou and Danzhou Baimajiang ports. A 2016 report in the PLA-run paper China Defense News indicates that the Sansha Garrison uses militia bases on the Hainan mainland to train militiamen in navigation, communications, and other skills.

Ships resembling the “Qiongsanshayu” vessels also feature in a music video produced by the Sansha Garrison, called “Song of the Sansha Maritime Militia,” which depicts the city’s maritime militia training with weapons, performing surveillance, carrying out boarding operations, and engaging in other such activities.

According to recruitment paperwork from 2015, Sansha City Fisheries Development has prioritized hiring PLA veterans to crew its ships. In fact, in 2019 the Hainan Department of Veterans Affairs recognized the company as a “model unit” for PLA veterans.

Using AIS data and satellite imagery, RFA tracked 18 different “Qiongsanshayu” vessels carrying out deployments in the South China Sea over the last year. These include deployments alongside the China Coast Guard (CCG) to Scarborough Shoal in April 2021 by the Qiongsanshayu 00402 and the Qiongsanshayu 00317, which sailed out together from Danzhou Baimajiang in March. China uses CCG and militia vessels to maintain a continuous presence at Scarborough Shoal, which it has effectively controlled since a standoff with the Philippines in 2012. According to the Philippine government, the CCG harassed the Philippine Coast Guard near Scarborough Shoal on April 24 and 25.

Satellite images from April 24 showing what appears to be the Qiongsanshayu 00402 and Qiongsanshayu 00317 at Scarborough Shoal alongside two CCG ships, the China Coast Guard 3303 and Zhong Guo Hai Jian 71. Credit: Planet Labs, Inc.; Analysis: RFA

More recently, a group of at least nine ships from the “Qiongsanshayu” fleet departed from the Sanya Yazhou, Wenchang Qinglan, and Danzhou Baimajiang ports on April 23, reaching the Spratly Islands by around April 25. This group included “Qiongsanshayu” vessels numbered 00206, 00208, 00212, 00214, 00223, 00227, 00228, 00232, and 00401.

Vessels from the “Qiongsanshayu” fleet also participated in the Haiyang Dizhi 8 standoff between Vietnam and China near Vanguard Bank in 2019, have carried out joint rescue operations with the PLA Navy South Sea Fleet, and have participated in joint exercises with Sansha City’s local maritime law enforcement force, according to AIS data, Chinese government bulletins, and other such sources.

Experimental systems and foreign technology

Some of the communications technology installed on ships in the “Qiongsanshayu” fleet also indicate that they are more than just ordinary fishing boats.

The Hainan Communications Administration recently led a project to test a shipborne “emergency satellite command and communications” system for maritime law enforcement, fishing, and emergency management in the South China Sea, according to a February 2018 environmental impact assessment.

The ultimate goal of this project was to build satellite links between shipborne systems, ground communications networks, and an emergency command center, effectively extending flows of information to and from distant areas of the contested South China Sea.

More recently, a group of at least nine ships from the “Qiongsanshayu” fleet departed from the Sanya Yazhou, Wenchang Qinglan, and Danzhou Baimajiang ports on April 23, reaching the Spratly Islands by around April 25. This group included “Qiongsanshayu” vessels numbered 00206, 00208, 00212, 00214, 00223, 00227, 00228, 00232, and 00401.

Vessels from the “Qiongsanshayu” fleet also participated in the Haiyang Dizhi 8 standoff between Vietnam and China near Vanguard Bank in 2019, have carried out joint rescue operations with the PLA Navy South Sea Fleet, and have participated in joint exercises with Sansha City’s local maritime law enforcement force, according to AIS data, Chinese government bulletins, and other such sources.

Experimental systems and foreign technology

Some of the communications technology installed on ships in the “Qiongsanshayu” fleet also indicate that they are more than just ordinary fishing boats.

The Hainan Communications Administration recently led a project to test a shipborne “emergency satellite command and communications” system for maritime law enforcement, fishing, and emergency management in the South China Sea, according to a February 2018 environmental impact assessment.

The ultimate goal of this project was to build satellite links between shipborne systems, ground communications networks, and an emergency command center, effectively extending flows of information to and from distant areas of the contested South China Sea.

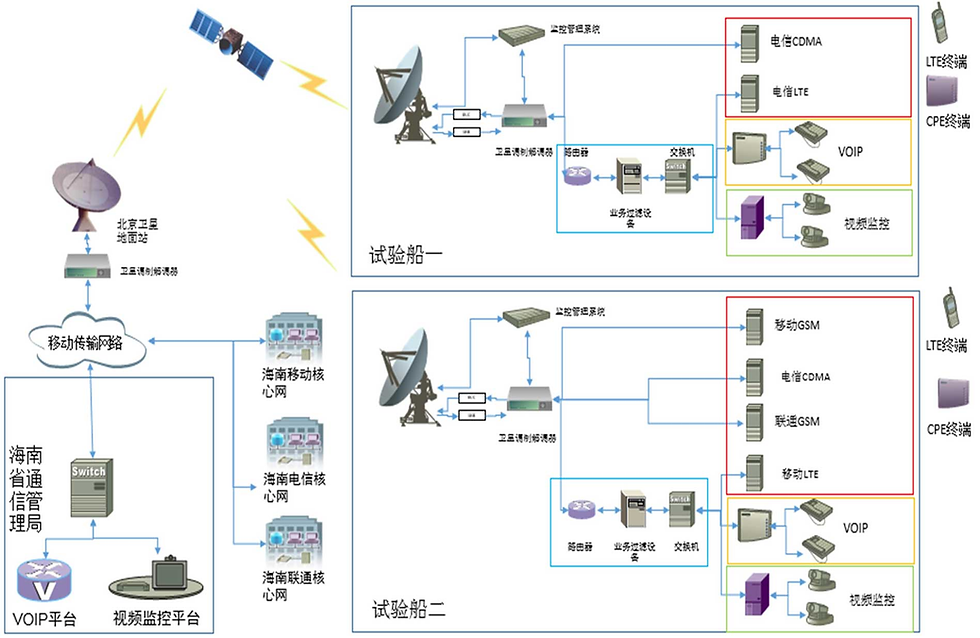

Diagram of the emergency satellite command and communications test ship system. Credit: Environmental impact assessment commissioned by the Hainan Communications Administration

With approval from China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, this experimental system was to be installed on the Qiongsanshayu 00209 and one of Sansha City’s supply ships, the Qiongsha 3. It included new hardware and software to realize localized mobile communications coverage, voice communications, video surveillance, data transmission, and other capabilities.

The environmental impact assessment states that the Qiongsanshayu 00209 belongs to Sansha City Fisheries Development, is 58.5 meters long and 9.2 meters wide, and has a 20-person crew. It implies that the Qiongsanshayu is based at Wenchang Qinglan, providing a picture of the ship moored at port.

Photo of the Qiongsanshayu 00209. Credit: Environmental Impact assessment commissioned by the Hainan Communications Administration

This is not the only case of ostensibly civilian vessels being equipped with high-end surveillance and communications technology. RFA has reported that Sansha City is installing similar systems on its Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 supply ships for the explicit purpose of tracking vessels from the United States, Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Taiwan.

The experimental system on the Qiongsanshayu 00209 even uses foreign satellite technology originating with companies from the United States, South Korea, and Japan, the 2018 environmental impact assessment shows.

The technology includes a KNS-Z12 satellite antenna from KNS Inc., a South Korean company; a POB-KUS100 upconverter from Wavestream, a U.S. company; a NJR2836U low-noise block downconverter from Japan Radio Company, a Japanese company; and a CDD 562AL satellite modem, a CDM 570A/L satellite modem, a CDM 625A satellite modem, and a CRS 170A switch from Comtech EF Data, a U.S. company.

Contracting records show that both Wavestream and Comtech EF Data are U.S. defense contractors, and the website of Comtech EF Data claims that the company has worked on numerous programs for clients like the U.S. Navy, U.S. Army, U.S. Air Force, and U.S. Marines.

That means satellite communications technology from U.S. defense contractors might be supporting the operations of Sansha City’s maritime militia in the South China Sea.

This is not the first time China has obtained foreign technology for use in South China Sea. A recent report by RFA revealed that Sansha City has acquired over $930,000 of foreign hardware, equipment, software, and materials. And in a separate investigation, this reporter found that Sansha’s local maritime law enforcement force is also using satellite communications technology from a U.S. defense contractor.

Fake fishermen

RFA also uncovered clear evidence of overlap between the fishermen living on islands and reefs occupied by China and the maritime militia personnel charged with guarding those features.

A bulletin board introducing Woody Island’s maritime militia company, visible in a community center used by fishermen living on Woody Island. Credit: mafengwo.cn, dajiangdahai

RFA compared Chinese state media reporting on Sansha’s maritime militia to the corporate records associated with 106 small-scale “aquatic product and fishing businesses” registered in Sansha as well as several fishing cooperatives registered in the city.

In total, RFA found 13 members of Sansha City’s maritime militia who appear to run “aquatic product and fishing businesses” or are listed as staff for one of the city’s fishing cooperatives. Nine of these militiamen are associated with both an “aquatic product and fishing business” and a fishing cooperative.

These individuals include 10 militiamen of unspecific rank, one militia squad leader, one militia platoon sergeant, and one militia company commander, each located on one of five features in the Paracel Islands, namely Woody Island, Yagong Island, Robert Island, Observation Bank, and Tree Island, according to Chinese state media.

Of the “aquatic product and fishing businesses” run by militiamen, all are registered to addresses in residential areas used by Chinese fishermen on Woody Island, Yagong Island, Robert Island, Observation Bank, and Tree Island.

Map of the Paracel Islands showing the locations and names of the 13 militiamen that RFA identified. Credit: Google Earth; Analysis: RFA

The registered address of each small-scale fishing company aligns with the reported location of its associated militiaman, such as the “aquatic product and fishing business” registered to Robert Island by Chen Daming, who Xinhua News describes as a Robert Island-based militiaman.

These militiamen are likely fishermen who received military training.

In a proposal published in 2014, Sansha City’s delegation to the Hainan Province People’s Congress admitted that the city was training fishermen to guard the islands and reefs within the city’s jurisdiction. The proposal further explained that “regardless of whether they are fishermen operating in distant seas or fishermen engaged in aquaculture or other activities, they can all become well-trained militiamen and receive corresponding subsidies.”

China Defense News described one of the militiamen that RFA identified, Xu Mingwen, as an “old fisherman” now operating radar and video surveillance equipment in Tree Island’s militia post. According to a report by PLA Daily, this post feeds intelligence back to a PLA command center on Woody Island.

A “Sansha Militia” patch visible on the sleeve of a militiaman carrying out surveillance from a militia post. Credit: Political Department of the PLA Hainan Province Sansha Garrison

Similarly, a 2016 article from China Youth Daily implies that a militiaman verified by RFA, Ye Jun, was a fisherman who received militia training on Yagong Island from the Sansha Garrison, which included boat piloting, engine repair, communications, and wound treatment.

From their postings on the front lines of the South China Sea, these 13 fishermen-turned-militiamen appear to have played an active role in defending China’s claims.

Another militiaman that RFA identified, Woody Island-based Lu Le, was interviewed in 2013 by China National Radio. He said that while navigating the waters of the Paracel Islands in April 2013, he spotted a foreign fishing boat “illegally entering” China’s “territorial waters.” Lu proceeded to report the foreign vessel to the Sansha Garrison, which then mobilized nearby maritime law enforcement ships to chase it away — a clear example of Sansha City’s “military, law enforcement, and civilian joint defense” system in action.

A China National Radio reporter (left) interviewing militiaman Lu Le (right) in 2013. Credit: China National Radio

And Xinhua News reports that Yagong Island-based Xu Dezhi, yet another militiaman identified by RFA, was injured in August 2014 while boarding a foreign fishing boat. According to Xinhua, Xu was out fishing when he discovered the foreign vessel. He proceeded to board the fishing boat and cut his wrist during the ensuing fight with the boat’s crew.

RFA also tracked down Observation Bank Militia Company Commander Li Linjun, who received a gash to the right arm from a harpoon during a hand-to-hand scuffle after chasing and boarding a foreign fishing boat in July 2015, China Youth Daily reported.

It is no wonder that Sansha City’s party secretary and mayor, Xiao Jie, once described the city’s maritime militia as part of a “Great Wall of Steel” in the South China Sea.

How China is Leveraging Foreign Technology to Dominate the South China Sea

Cutting edge technology from the United States and other foreign countries is helping China assert its sweeping maritime and territorial claims in the contested South China Sea, a Radio Free Asia investigation has found.

Chinese government procurement contracts reveal that Sansha City — which administers China’s outposts in the Paracel and Spratly islands — has acquired or plans to acquire hardware, equipment, software, and materials from at least 25 different companies based in the U.S. and other countries. These items have applications in maritime law enforcement, information security, land and sea surveillance, and other areas.

For example, the city is currently set to acquire an unmanned surface vehicle — the maritime equivalent to an aerial drone — that includes components from several U.S. companies. Such a vehicle might be used to track and possibly even intercept vessels from rival South China Sea claimants like Vietnam and the Philippines.

In total, 10 Chinese party-state entities associated with Sansha City have acquired or currently plan to acquire up to 66 items worth over 6,540,000 yuan ($930,000) for use in the South China Sea, according to 13 government contracts and other associated documents. All of these contracts were signed between late 2016 and early 2021, with the majority of items coming from contracts inked in 2020.

The cost of foreign technology acquired by Sansha City broken down by country and year. Not every contract provided cost data for every item; "reported cost" refers to items that did indeed have a specific yuan value. Credit: RFA

The Chinese government’s long-standing practice of acquiring foreign technology to advance its strategic goals is a major source of tension in U.S.-China relations, with U.S. authorities turning to export controls and other tools to stem the tide of transfers. But according to experts that RFA spoke to, most of the items that Sansha City obtained from U.S. companies are unlikely to be covered by existing export control measures.

But there is one possible exception: the city appears to have acquired a counter-surveillance device from a U.S. company that could be used to protect China’s communications from unwelcome eavesdropping — including from intelligence specialists in the U.S. military who closely monitor China’s facilities in the South China Sea. This device and other equipment in the same product line have been supplied to a variety of U.S. government and military customers, contracting records show.

Map showing the South China Sea region and claimant states, as well as China's nine-dash line claim that covers most of the South China Sea. Credit: RFA

Scooping up foreign tech

China regards Sansha City as having jurisdiction over about 2 million square kilometers (800,000 square miles) of sea and land — the bulk of China’s claims in the South China Sea, where the People’s Republic is entangled in maritime and territorial disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei.

From their headquarters on Woody Island in the Paracel Islands, the leaders of Sansha City manage day-to-day affairs on China’s remote outposts and oversee the implementation of long-term initiatives, working with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to develop infrastructure, defense capabilities, transportation, and communications as part of a "military-civil fusion" strategy.

Satellite image from December 2020 showing Woody Island in the Paracel Islands, which serves as the central hub of Sansha City. Credit: Planet Labs, Inc.

RFA found that Sansha City has acquired or plans to acquire technology from at least 25 different companies based in the United States, Sweden, Austria, Italy, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Taiwan, with the majority of items coming from U.S. companies.

And the 13 procurement documents from Sansha City that RFA identified may just be the tip of the iceberg. In 2020 alone, the city generated over 700 bidding announcements, contracts, and other similar documents that could contain evidence of technology transfer.

The city obtains these items through third-party Chinese companies. How exactly these Chinese companies acquire the technology from foreign companies, however, remains unclear.

RFA contacted every foreign company named in Sansha City’s procurement contracts. Of the companies that responded, several said that they do not directly oversee their operations in China, instead working through networks of distributors. Others stated that their contracts preclude them from providing information on specific sales, denied having any relationship with the companies supplying Sansha, or otherwise declined to comment on the story. As such, RFA could not independently verify transfers of technology from foreign companies to Sansha.

Map showing the home countries of foreign companies named in Sansha City’s procurement contracts. Credit: RFA

Zetron, which is headquartered in the United States and whose products Sansha obtained for use in maritime communications infrastructure, exemplifies this ambiguous procurement chain. Zetron said that it is “contractually prohibited from divulging specific customer or system information.” But it also said that “Zetron systems sold and installed in the Asia Pacific region are done so by Zetron Australasia Ltd., which is a separate legal entity from Zetron, Inc. and is headquartered in Australia. So any Zetron systems sold in that region are done so from there, versus Zetron, Inc. here in the U.S.”

Similarly, Airmar, whose weather monitoring device is to be used by Sansha in an unmanned surface vehicle, said that “our products are sold and resold through a distribution chain around the world” and that “Airmar does not always have the ability to track where our products have ultimately ended up.”

Many of the foreign companies are multinational corporations, some with sales offices or other subsidiaries in China, which further obfuscates the transfer process. For example, one of Sansha City’s contracts explicitly names the U.S. branch of Navico, a company headquartered in Norway with offices across the globe, including in China.

Diagram showing how Sansha City procures technology from foreign companies through third-party Chinese companies. Credit: RFA

From maritime patrols to tracking turtles

The foreign technology acquired by Sansha City has applications in a number of different areas, all of which support China’s interests in the South China Sea.

About a quarter of the items are designated for use in maritime law enforcement vessels: patrol boats, shipborne boats (smaller craft that are deployed from larger ships), assault boats, and unmanned surface vehicles. Sansha City uses these vessels to patrol its jurisdiction and assert China’s claims at the expense of other claimants.

Other items are intended for less sensitive uses, such as environmental and ecological monitoring, but even those activities may ultimately help strengthen China’s capacity to control contested areas.

Application areas of technology acquired by Sansha City. Credit: RFA

For example, according to a contract from 2017, the city acquired equipment from U.S.-based Strix Systems for a wireless self-organizing network, which was to be used alongside numerous components from Chinese companies for a sea turtle monitoring system in the Qilian Islets in the Paracel Islands. According to the contract, the city planned to integrate this sea turtle monitoring system into a broader monitoring platform on Tree Island, another China-occupied feature in the Paracels. According to reporting in PLA Daily, a paper run by the Chinese military, maritime militia forces use monitoring capabilities on Tree Island to surveil nearby waters and feed intelligence back to a PLA command center on Woody Island.

While in many cases the foreign technology is used in combination with Chinese components, in others, Sansha City has procured entire systems from foreign companies. For instance, in 2020, the city’s hospital signed a contract with a Chinese company to acquire an automatic biochemical analyzer from Hitachi. This hospital serves PLA personnel stationed on Woody Island and coordinates 5G-based telemedicine services with the Hainan branch of the PLA General Hospital.

Examples of specific items that Sansha City has obtained or plans to obtain for use in maritime law enforcement. Credit: RFA

Examples of specific items that Sansha City has obtained or plans to obtain for use in monitoring land and sea areas. Credit: RFA

"Look Out" for unmanned vessels

Among the most consequential uses of foreign technology by Sansha City is in the L30 unmanned surface vehicle, sometimes called the “Look Out.”

The developer, Zhuhai Yunzhou Intelligent Science and Technology Co., Ltd, says the 7.5-meter-long vessel can travel up to 310 nautical miles, reach speeds of 40 knots, and operate autonomously or with a human crew. It also can mount an automatic weapon station or a precision missile launcher capable of hitting targets up to five kilometers away.

The Chinese L30 unmanned surface vehicle, which includes technology from U.S. companies, outfitted with an “automatic weapon station” as seen in a promotional video on the website of its Chinese developer, Yunzhou. Credit: www.yunzhou-tech.com

State-run broadcaster China National Radio reported in 2018 that the L30 is designed to carry out duties including reconnaissance, precision strikes, and guarding islands and reefs as well as their surrounding waters. It touted the vessel as a triumph of indigenous innovation: China’s “first maritime weapons platform jointly developed by a local private military industry company and a state-owned military industry research institute.”

And though Yunzhou claims to be a leader in the field of unmanned surface vehicles, the L30 ordered by Sansha City includes 1,635,000 yuan ($233,571) of key components from three U.S. companies and one Austrian company: an automatic identification system (AIS) transponder from the U.S. branch of Navico, a weather monitoring instrument from Airmar, two drives from Mercury Marine, and two diesel engines from the Austrian company Steyr Motors.

Yunzhou is due to deliver a single L30 to Sansha City’s coast guard force before July 2021, at a total cost of 5,102,600 yuan ($730,000), according to the contract. This coast guard force works with China’s maritime militia, the PLA, and the China Coast Guard (CCG) to surveil Sansha’s jurisdiction and uphold China’s maritime claims.

The L30 with two Mercury Marine drives as seen at the China International Aviation and Aerospace Exposition in 2018 (left) and a promotional video on Yunzhou's website (right). Credit: PRC Ministry of National Defense, www.mercurymarine.com, www.yunzhou-tech.com

The L30, under the name of “Look Out II,” armed with a missile launcher as seen at the China International Aviation and Aerospace Exposition in 2018. Credit: PRC Ministry of National Defense

China National Radio reports that Yunzhou jointly developed the L30 with the Huazhong Photoelectric Technology Research Institute, which belongs to China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC), a major state-owned defense contractor. In December 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce restricted exports to this research institute, also known as the CSSC 717th Research Institute, for “acquiring and attempting to acquire U.S.-origin items in support of programs for the People’s Liberation Army.”

This unmanned surface vehicle will be just the latest high-tech system deployed by China to monitor and control contest areas like the Paracel and Spratly islands.

According to J. Michael Dahm of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, China’s outposts in the Spratly Islands are bristling with communications and reconnaissance capabilities, which “provide the Chinese military and maritime law enforcement with the same level of knowledge and control in the Spratly Islands that they have in Chinese territorial waters.”

And some of these capabilities rely on foreign technology too. A recent investigation published in the Jamestown Foundation’s China Brief by this reporter, for instance, revealed that Sansha City’s coast guard force uses a satellite communications system built around hardware from a U.S. defense contractor.

U.S. tech helping China keep secrets

RFA’s investigation also found that Sansha City is exploiting U.S. technology to safeguard sensitive state secrets.

Under a December 2018 contract, Landun Information Security Technology Co., Ltd. agreed to provide 640,500 yuan ($91,500) of communications security equipment to the Office of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Sansha Committee, which is the main decision-making body in Sansha and has overlapping leadership with the city’s PLA garrison.

Photo published in 2015 showing PLA leaders and local officials discussing Sansha City’s maritime security. Credit: National Defense

The bundle of equipment includes two pieces of foreign technology: a camera detection device, the “Suresafe/VS-125,” which is likely from Suresafe, a Taiwanese company; and a digital phone and line analyzer, the “REI/DPA-7000,” which appears to be from Research Electronics International, a U.S. company.

A document available on Research Electronics International’s website describes the “DPA-7000 TALAN Telephone and Line Analyzer” as a “state-of-the-art capability to rapidly and reliably detect and locate illicit tampering and security vulnerabilities on both digital and analog telephone systems.” It adds that the device “provides a suite of tools in a single piece of equipment to accurately analyze phones and lines for faults and security breaches.”

In 2017, Research Electronics International launched an updated version of the TALAN, which has the same basic capabilities as the older DPA-7000. The newer TALAN 3.0 has applications in technical surveillance countermeasures, wiretap detection, eavesdropping detection, intelligence protection, surveillance equipment detection, and electronic surveillance detection, the company’s website says.

Picture of the DPA-7000 TALAN Telephone and Line Analyzer from a product brochure on the website of Research Electronics International. Credit: reiusa.net

Publicly available contracting records show that Research Electronics International has supplied the TALAN line of products to numerous U.S. government and military customers. These include the Federal Bureau of Investigations, the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, and the U.S Coast Guard — specifically the Coast Guard Counterintelligence Service.

This suggests that Sansha City might be leveraging counter-surveillance technology from a U.S. defense contractor to secure the city’s communications against U.S. signals intelligence collection efforts.

U.S. intelligence collection in the South China Sea region has long rankled the PLA, which maintains numerous sensitive facilities in the area, ranging from submarine bases to missile sites. Over the past 20 years, Chinese forces have repeatedly intercepted U.S. intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms operating in or above the South China Sea. These interceptions have caused major incidents on several occasions, like in 2001 when a PLA fighter crashed into a U.S. EP-3 signals intelligence aircraft, killing the Chinese pilot and forcing the U.S. plane to perform an emergency landing in Chinese territory.

Tech transfer feeding tensions

According to experts, Sansha City’s efforts to acquire foreign technology mirror longstanding Chinese government practices, which have become a major source of tension in U.S.-China relations and emerged as a priority for the new Biden administration.

For several decades, China has systematically acquired technology from the United States, Japan, Germany, and other advanced economies in a bid to boost domestic industries and facilitate an ambitious military modernization program.

Photo from 2019 showing the Shandong, China’s first domestically produced aircraft carrier. Credit: Xinhua News

Emily Weinstein, a research analyst at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, told RFA that China acquires foreign technology through “legal, illegal, and extralegal means.”

“These can involve everything from M&A [mergers and acquisitions] and investments, to copyright infringement and traditional espionage activities, to gray areas like front organizations and United Front operations like professional associations and overseas scholar returnee organizations,” Weinstein said.

According to Ashley Feng, a specialist on U.S.-China economic relations, transfers of technology to China have security as well as economic implications, making them a major concern for U.S. authorities.

The U.S. government uses a range of tools to impede these transfers, including export control mechanisms. “Through the Export Administration Regulations, the Munitions List, the Commerce Control List, and the Entity List, the U.S. government can control what technology is exported out of the United States both by where the export will end up and/or whose hands it will end up in,” said Feng.

In recent years, the U.S. government has pursued export control reforms aimed at China and repeatedly placed restrictions on specific Chinese entities. For instance, since August 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce has repeatedly restricted exports to Chinese companies for their roles in building artificial islands, militarizing occupied features, and supporting coercion against other claimants in the South China Sea.

Experts told RFA that the items acquired from U.S. companies by Sansha City are unlikely to be covered by existing export control measures. “At first blush these appear to be technologies just below the controls threshold,” explained James Mulvenon, director of intelligence integration at defense contracting firm SOS International, who described these types of transfers as a “vexing problem” for the U.S. government.

“But the civilian nature of the purchase is simply part of the Potemkin nature of the Sansha political entity, which was only created to give a demilitarized, civilian cover for what is more accurately a military occupation of disputed possessions,” Mulvenon said.

But there is one potential outlier: the countersurveillance device that Sansha City appears to have acquired from Research Electronic International. According to the company’s website, the DPA-7000 TALAN Telephone and Line Analyzer falls under export control classification number (ECCN) 5A992.b, which suggests that relevant U.S. authorities may view the device as a sensitive item subject to certain export restrictions on national security grounds, though this particular ECCN is outdated thanks to reforms in 2016.

The U.S. Department of Commerce did not respond to RFA’s request for comment.

Research Electronics International told RFA that “all of our sales, throughout the world, are made in full compliance with the law and US export regulations” and that “we have no records of the companies you are inquiring about and we have not made any sales to Sansha City.”

If the company’s statement is accurate, then Sansha City may have acquired the DPA-7000 through illicit means. According to Mulvenon, “China uses a wide array of strategies to get this tech, but the sensitive nature of the South China Sea issue makes it more likely for them to use cutouts and front companies and then divert the technology to the real destination and purpose.”

Sansha City’s acquisitions of foreign technology, licit or otherwise, appear poised to continue unabated. In late February, the city signed a procurement contract for three maritime law enforcement patrol boats, which are slated to use outboard engines, communications equipment, night vision devices, and other components from companies in the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Japan.

That means, unless the U.S. government and other relevant authorities take action, China’s efforts to dominate the South China Sea will continue to be supported by foreign technology.

The Chinese digital octopus spreading its tentacles through smart port ambitions

As the world of shipping has moved towards smart ports, China has quietly been strengthening its position of power over global trade via its data aggregation platform that has been embedded into port and terminal operating systems.

Initially, the level of data exchange and interface required was built around China’s ambitions of being a regional hegemon through the Belt and Road Initiative. Initially described as an opaque system that merely sought to create “win-win” trade solutions, many port operators began to engage with China’s digital platforms.

Over time many started to see China’s introduction of the Digital Silk Road as a co-ordination platform for trade along the Belt and Road. Naively, many port and terminal operators began embracing the cheaper and more advanced China digital interface platforms. The safety and security of data issues became paramount in the debate.

These earlier concerns around supply chain integrity and security have now been escalated as governments begin to understand the full implications of LOGINK being the underpinning data platform of digital interfaces within smart port development. The discussion around meritocratic processes in technical and data sharing standards creation has shifted to one around logistics / supply chain integrity. With greater data sharing and system interoperability there is greater risk to data / information integrity as the smart port agenda has been subsumed under China’s digital silk road strategy in which ports have been instrumental in furthering China’s agenda.

Unfortunately, the open (the West) and closed (China) digital systems are entering a phase in which national agendas take precedence over transparency and visibility within global trade. This has been exacerbated by the increase in the expanse and use of the China LOGINK platform, much of which has gone unnoticed. What was a hidden data platform has now become increasingly visible as its tentacles have now enveloped up to 75% of global trade.

How has LOGINK achieved this level of penetration? Through engagement with ports, LOGINK can now be found in over 50 countries and spans every global logistics network. This spread has gone beyond port ecosystems but now includes railways and other transport networks. China has strategically focused on European ports as it seeks to carve the US out of the EU economy.

The spread is now a major concern to the EU as it begins to understand the extent of the potential risks to EU / China trade through supply chains vulnerability. More importantly there is an understanding by the EU that the level of port penetration by LOGINK makes Europe more susceptible to Chinese economic coercion through data manipulation. European ports have accelerated this risk with LOGINK now having a network of 31 European ports in which China can influence trade flows.

There is additional pressure as China ramps up its Taiwan ambitions, particularly when taking account of China’s civil-military fusion strategy. There are ports within the LOGINK network that include US naval facilities, including the ports of Antwerp, Zeebrugge, Valencia, Le Havre, Amsterdam, Gydnia and Stockholm. This presents a significant trade security risk should China wish to block the Taiwan Strait through military intervention and use data manipulation to effectively stop a response from these naval based ports.

Compounding the issue has been the expansion of China’s digital footprint through the integration of LOGINK into the port operating systems: CargoSmart and CaiNao (Alibaba). Integration within these platforms was made possible through China’s Transport and Telecommunications and Information Center partnership with the International Port Community Systems Association. This partnership created data sharing standards for countries that allowed for seamless data sharing interfaces.

As the role of ports in advancing China’s geo-economic ambitions is being analysed and understood, there has been a divergence in response by the US and EU. This divergence has potential future consequences for trade between these two economic blocks.

Initially the US has responded to this perceived threat by banning the Pentagon from using any port worldwide that has a digital interface or handshake with China’s LOGINK. This may well extend to any trade item that becomes defined as of strategic national importance. Examples could include shipments of rare earths, semi-conductor trade.

On the other hand, the EU has been more reserved in its response. The response has been shaped by the spread and integration of China’s trade within the EU and the direct LOGINK partnership in 24 European ports. Essentially the network and spread with European ports is making US / EU and global trade more complex. It is becoming evident that businesses will need to find ways to bypass the use of LOGINK or formulating APIs within these ports that allow a secure interface between port operating systems.

In the short to medium term, there is likely to be an increased use of data / information coercion to achieve global trade goals and economic dominance. Currently, it looks like China has used LOGINK to get in front of the West, securing a position of strength over strategic logistics and supply routes.

As global trade becomes increasingly digitally integrated, there needs to be a greater awareness of the power of that data and how it can be used. Companies need to be aware of these developments such that they have robust API software in place that will enable effective data exchange without compromising the security of their supply chains. The horse may well and truly bolt in terms of a weaponised LOGINK, but it is never too late to put systems in place that make you less vulnerable to economic coercion and / or trade manipulation.

Espionage & National security: China planted mystery devices on cranes used in US ports, could seize control remotely. US Congressional Letter

The devices ‘do not contribute to the operation of the STS cranes or maritime infrastructure and are not part of any existing contract,’ the letter said. In the meantime, as always in Europe and Italy all is silent. National security remains taboo even in the face of evidence.

Top Republicans from multiple House committees are sounding the alarm on a series of mysterious devices that appear to have been implanted into container cranes used throughout the U.S. port system by China.

The lawmakers say that numerous modems with no known function were uncovered from ship-to-shore (STS) cranes, which are used to unload cargo at the nation’s largest ports.

All of the cranes in question were manufactured by Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries (ZPMC), a subsidiary of the state-owned China Communications Construction Co.

Relatedly, the lawmakers noted that ZPMC’s manufacturing facility is located adjacent to China’s most advanced ship-making facility, where the regime builds its aircraft carriers and houses advanced intelligence capabilities.

In a letter (pdf) addressed to the president and chairman of ZPMC, the lawmakers demand to know the purpose of the cellular modems discovered on crane components and in a U.S. seaport’s server room that houses firewall and networking equipment.

“These components do not contribute to the operation of the STS cranes or maritime infrastructure and are not part of any existing contract between ZPMC and the receiving U.S. maritime port,” the letter said.

“The Committees have serious concerns that this proximity to the [Chinese military’s] main shipyard provides malicious CCP [Chinese Communist Party] entities, including its intelligence agencies and security services, with ample opportunity to modify U.S.-bound maritime equipment, exploit it to malfunction, or otherwise facilitate cyber espionage thereby compromising U.S. maritime critical infrastructure.”

U.S. Coast Guard Rear Adm. John Vann, who leads the Coast Guard’s Cyber Command, told reporters last month that there were over 200 China-manufactured cranes operating across U.S. ports and regulated facilities.

At that time, Coast Guard cyber protection teams had assessed the cybersecurity or hunted for threats on 92 of those cranes, he said.

The discovery comes amid an ongoing congressional investigation into the operation of cranes manufactured in China and operating at U.S. ports.

Though the investigation is still ongoing, the committees identified serious concerns regarding ZPMC’s relationship with the CCP, particularly given the recent discovery of Chinese malware on vital infrastructure related to the port system.

As part of another cybersecurity investigation, some of the modems in question were also found to have active connections to the operational components of the STS cranes, suggesting they could be remotely controlled by a device no one previously knew was there.

Speaking to reporters last month, White House Deputy National Security Adviser Anne Neuberger said the cranes were designed to be serviceable from a remote location, which leaves them open to such exploitation.

“By design, these cranes may be controlled, serviced, and programmed from remote locations,” Ms. Neuberger said. “These features potentially leave [China]-manufactured cranes vulnerable to exploitation.

As such, the letter suggests that every U.S. seaport with ZPMC cranes could already be, or is at risk of being, compromised by the CCP.

Retired Army Col. John Mills told The Epoch Times that the cranes were effectively an extension of the CCP’s global cybercrime operation, which could be used during an invasion of Taiwan to sow chaos in the United States.

“Those container cranes are not cranes,” Mr. Mills said. “They’re IP endpoints on a worldwide intelligence collection system.”

To that end, he said that the cranes’ operational and safety features could likely be overridden remotely. This would allow the CCP to potentially trick one of the giant cranes into shifting its counterbalance in such a way that would cause it to crash into ships or containers in the nation’s busiest ports.

Complicating the issue all the more, he said, was the fact that the niche nature of the cargo cranes and their programming means it is unlikely a tailored cyber response to secure the systems will be created anytime soon.

To counter the threat in the long term, he added, the United States would need to ensure that it manufactured such vital equipment in its own territory.

“As things play out, they’re [the CCP] going to start initiating the hitting of target sets in cyber. The port cranes are a perfect example,” Mr. Mills said.

“This is the importance of making things here. If you want to reduce the Chinese threat, start making things here.”

Container weapon system: a "blind box of firepower" with enormous potential. Chinese EPL analysis

To achieve the goal of global expansion, Beijing also exploits the Belt and Road, including maritime.

History teaches that whoever controls the maritime trade controls the world.

To support force projection abroad, Beijing has developed a military strategy that requires the armed forces to routinize military activities across borders, encouraging the use of BRI investments, especially in ports, airports and railways.

Russian "Caliber-K" containerized weapons launching system

Russian "Caliber-K" container weapon launching system.

With the development of the modern logistics industry, containers are increasingly entering people's field of vision. They can be found on trucks, trains and docks along the coast.

If they had not paid much attention, not many would have thought that containers are also increasingly appearing on the battlefield. However, in addition to their basic function of transporting materials, many of these containers exist as weapons and some have even been used in actual combat.

In October 2023, the news that the U.S. Navy's Independence-class coastal combat ship USS Savannah had launched a "Standard-6" anti-aircraft missile into the Pacific Ocean attracted attention. One reason was that the missiles in question were test-launched from the Mk70 container system.

Israeli "Laura" containerized short-range missile reflector system

In June of that year, the French Navy conducted its first sea test of a containerized multi-purpose high-energy laser installed on the deck of a frigate, successfully destroying a small drone.

Many of the cruise missiles launched by the Russian Navy in some military operations in recent years came from the "Caliber-K" container weapon system mounted on surface ships.

Why are containerized weapons on the rise? What are its characteristics? How is the development going? Please read the interpretation.

Israeli "Laura" short-range container missile reflection system.

Follow the trend" transformation from mature civilian products.

For containers, storage and transshipment are the two basic functions. The realization of these two main functions has a basic premise, namely the standardization and universalization of containers.

This kind of standardization and generalization makes containers one of the important symbols of modern logistics. It can be transported in a variety of vehicles, allowing it to "go almost anywhere."

It is this characteristic of being able to "walk" and "stay" that makes containers the target of weapons developers, which has led to the creation of a variety of container weapons.

Israeli "Laura" containerized short-range missile reflector system

The so-called container weapon has not yet received a unified definition worldwide. Its most important feature is that, depending on the specifications and appearance of civilian containers, single or combined weapons are integrated into the container for ease of transport, deployment, and use.

What must be emphasized is that, unlike storage, weapons containers do not simply store weapons in "iron boxes," but integrate weapons with containers, including many auxiliary and support systems, in order to maximize weapons effectiveness.

Take for example the Russian Army's "Caliber-K" container weapon system, which first appeared at the Asian Defense Exhibition in Malaysia in 2010. It consists of a universal launch module, a combat command module and a logistics support module. Each module is integrated and can be mounted in a container on various platforms such as surface ships, rail trains and road vehicles.

In October 2015, the Russian Navy's Caspian Fleet launched at least 26 cruise missiles during an attack. What caught the attention of the outside world is that some of these cruise missiles were launched from the M-class light frigate "Thug" Type 21631 using the "Caliber-K" container weapon system, which is a typical "small boat carrying a big gun."

From small missile launchers of hundreds of tons to 1,000-ton patrol ships and light frigates to 3,000-ton multi-purpose frigates, "Calibre-K" has appeared on their decks, which shows that container weapons are not suitable for Custom.

Russia is also said to be planning to install two sets of "Calibre-K" container weapon systems on the stern of the Type 23550 icebreaker patrol ship to further strengthen its influence in the Arctic region.

The larger container volume allows larger weapons to be integrated. The Mk70 container weapon system tested by the U.S. Navy is improved from the Mk41 naval vertical launch system and can launch "Standard" and "Tomahawk" series missiles.

In October last year, the U.S. Navy's Independence-class coastal combat ship USS Savannah used the Mk70 container weapon system to test launch a "Standard-6" anti-aircraft missile and hit the target. This test is part of the U.S. Navy's exploration of the use of containerized weapons.

The Mk70 container weapon system is also one of the launch modules that make up the U.S. military's "medium-range strike capability." Currently, interested companies have delivered the weapon system to the first missile system launch company with "medium-range strike capability" of the U.S. military. In exercises conducted by European and American countries since 2022, combat vehicles equipped with Mk70 container weapon systems have been demonstrated several times.

The U.S. Marine Corps has launched a plan to integrate the RGM-184 missile on an amphibious assault ship and tested its launching technology through a container weapon system.

The container's large volume allows it not only to house weapon systems but also to integrate related power, detection, communication and control systems, making the container weapons more independent and flexible in use. At the same time, this larger volume also allows it to accommodate more weapon systems to some extent to address threats at different levels. For example, containerized long-range rocket launching systems produced by some countries can be loaded with rockets of different calibers to carry out targeted attacks against different targets.

From this perspective, container weapons are the product of mature civilian products being "exploited" and combined with weapon systems. This combination, in turn, has given rise to some new changes in containers.

For example, last year the U.S. Army demonstrated a laser-guided rocket launcher in an exercise. Although it is also a container weapon and four rockets can be integrated into a container, the length of this container is shorter, only 1/4 the length of the standard national 40-foot container, and its detection system is integrated into another similar container, which can be placed in different locations.

Battlefield suitability has become the driving force behind the rise of containerized weapons.

In September 2021, the U.S. Navy launched a "Standard-6" anti-aircraft missile from a container weapon on the unmanned ship USS Ranger in a test. This move means that the utility of containerized weapons has been further expanded, and they have begun to "sit" on unmanned platforms and essentially "join forces" with them.

The development of container weapons is reflected not only in the fact that they can be mounted on more and more platforms, but also in the fact that they "house" increasingly different types of weapons and equipment.

In terms of integrating containers with traditional weapons and equipment, more and more countries and companies have begun efforts.

The European company MBDA is engaged in developing the "Mistral" short-range container air defense system, seeking to deploy it on various types of combat ships.

Based on the "Laura" short-range missile, Israel has launched the development of a container missile reflection system and also plans to launch a sea-based container missile reflection system.

The Finnish company Patria has containerized the developed 120 mm NEMO mortar, realizing the "land-to-sea" system, including its use to confront enemy ships in shallow waters.

The British Navy has proposed the concept of "persistent combat deployment system" and plans to create a common architecture and unified interface to realize containerization of various firearms, drones and directed energy weapons and configure them flexibly on a variety of combat platforms .

Containerization is also a trend in the development of emerging and newly developed weapons.

Drones are popular weapons on modern battlefields. Currently, some countries and companies are promoting drone containerization. At the 2019 annual meeting of the Association of the United States Army, the U.S. company Kratos Unmanned Aerial Systems proposed the concept of "container drones" and planned to integrate the XQ-58A "Valkyrie" drone into a container. The Russian fixed-wing integrated combat and surveillance drone "Pirate" already has the ability to be launched from a special container loaded onto a Kamaz car.

At the same time, anti-drone systems are also developing in this direction.

The "Thor" high-power microwave weapon developed by the U.S. Air Force, the integrated anti-drone combat system released by the British company "Mars" in July last year, and the AARTOS anti-drone combat system developed by Germany are all " stored" in containers.

Some laser weapons and electronic warfare weapons also show their "enthusiasm" for containers. Many of the "Iron Beam" laser weapon systems developed by Israel and the Russian "Peresvet" laser weapon system are "housed" in containers mounted on vehicles. The Israeli Defense Research and Development Agency and the South Korean defense company Hanwha Group are also working on the development and containerization of laser weapon systems. In 2022, the main content of the "Electromagnetic Mobile Warfare Modular Kit" project launched by the U.S. Navy is the development of electronic warfare equipment that can be deployed in standard containers.

Why do containerized weapons show such a "rapidly growing" trend? Simply put, it simply meets the needs of future battlefields.

It meets the demand for high mobility in troop deployment. The characteristics of high-intensity engagement in modern warfare require that troops can be gathered quickly and deployed more flexibly, while the characteristics of container weapons that can be reached in multiple ways make their deployment quick and efficient.

It meets the needs of modular design of weapon systems. "One platform can do many things" is a direction for modern weapons and equipment development. Containerized weapons follow the trend toward modular use of associated payloads on larger platforms. A container weapon is a module that can be configured to be more effective through building blocks.

It meets the need to rapidly resupply a large number of combat platforms during wartime. In wartime, the demand for combat platforms increases. The "container weapons + civilian vehicles and ships" approach can "plug and play" to quickly integrate a large number of combat platforms to meet firepower and protection needs.

In addition, container weapons can be integrated into ordinary containers, making attacks more devious and sudden, factors that have contributed to the spread of container weapons.

Finland's 120 mm NEMO containerized mortar system.

Although it has flaws, it could still become a "firepower booster" on future battlefields.

Just like other weapons and equipment, which have advantages and disadvantages, container weapons do not offer all the advantages.

As research, development, and utilization have progressed, the development of this type of weapons and equipment has also revealed some problems.

It must be relatively independent and platform compatible, which increases its cost. One of the characteristics of container arms is that they are "easy to transplant" and "plug and play," so they require a high degree of operational independence. This results in the container having to collect more equipment. In addition, the higher the requirements for weapon performance, the more software and hardware will have to be integrated: the result of "building a dojo in a snail shell" is reflected in the costs and the investment will increase accordingly. Especially to reach a level where each has the ability to network or even integrate into a higher level system, costs will continue to rise.

Containerized weapons are larger in size and will affect the efficiency of using the ship's deck. In the case of container weapons mounted on the deck of a ship, they can provide additional firepower or protection to the ship, but at the same time the container is larger, occupies a certain area of the deck, and is usually heavier. is The occupation of deck space can affect the use of other weapons and equipment on the ship, such as combat aircraft.

It can raise ethical issues in warfare. Although containerized weapons can be mixed in civilian containers to improve one's survivability and speed of attack, and make the adversary's attack less targeted like "removing a blind box," this "mixing" can also lead to attacks against the container. affected some civilians living in container houses, raising ethical issues in warfare.

Container weapons have weak protection. For some armored transport vehicles, the other side of the emphasis on "big belly and capacity" is the lack of protection. Containerized weapons also have this problem. Although some container weapons can be equipped with armor, this measure has some limitations and is almost useless in the face of some high-powered ammunition. These problems will affect the development of container weapons to some extent.

Nevertheless, containerized weapons are still developing rapidly. Due to its characteristics of ease of transportation, absence of "supports" and low cost, it could still become a "firepower booster" on the future battlefield.

The following parts are taken from the book "Xi Jinping's China. Toward a New Sinocentric World Order?", Nicola and Gabriele Iuvinale, Antonio Stango Publisher, 2023

Control over the most important European ports of NATO countries

Chinese presence and influence has expanded throughout the Atlantic.

Pact states through gigantic projects conceived under the Belt and Road Initiative, including maritime, which include participation, purchase or lease of ports overlooking the Mediterranean, some of which are also used by NATO.

China has long controlled the Greek port of Piraeus and finances highway and rail projects between the Balkan countries and Hungary.

There is Chinese investment in the world's 50 largest ports, especially in Europe. Rilevant, then, is the dangerous military-civil fusion project, which is one of the guiding principles of Xi Jinping's geopolitical action.

Growing fusion is a key component of China's logistical support to increase the PLA's military deployments and overseas activities. The National Defense Transportation Law, passed in September 2016, improved the People's Liberation Army's ability to leverage civilian vet- tors to support expeditionary operations and force projection by "imposing obligations on Chinese transportation companies located abroad or engaged in international overseas expeditions." The law also requires large and medium-sized Chinese companies to provide "support for rapid, longdistance, large-scale national defense transportation".